An Example of Perfect Government: The Life of Laura Kellogg

Posted by Pete on Sep 10th 2024

The Native American radical who led the fight for the return of indigenous lands and self-government

“The Iroquois are struggling for a renaissance. If we were permitted the return of self-rule, we could place before the world an example of perfect government.”

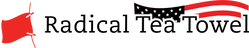

Indigenous resistance in the United States did not end with the military defeat of warriors like Tecumseh and Crazy Horse during the nineteenth century.

Indigenous radicals carried on the struggle by different means in the early twentieth century.

Laura Cornelius Kellogg was born on this day in 1880, on the Oneida Indian Reservation in Wisconsin.

Kellogg helped found the modern American Indian movement.

Kellogg fought for sovereignty, tribal autonomy and self-government in Native American lands

Kellogg was descended from respected Oneida chiefs like Daniel Bread, who had found new land for their people after they were ethnically cleansed from New York state by European settlers during the 1820s and 1830s.

Looking back to such ancestors, Laura Kellogg had immense pride in her Iroquois Nations, specifically, and Native America in general.

She would never accept the colonial lie that the indigenous people of North America were less civilised than Europeans.

Despite the fact she excelled at several U.S. educational institutions, including Stanford and Columbia, Kellogg always maintained that:

“…there are old Indians who have never seen the inside of a classroom whom I consider far more educated than the young Indian with his knowledge of Latin and algebra.”

This recognition of the enduring value of indigenous culture and knowledge set Kellogg apart from some of her contemporaries in the American Indian movement.

Tecumseh fought against the expansion of the United States onto Native American land, but the struggle continued long after his death in 1812

Other indigenous activists argued that the way to dignity and freedom for Native Americans was in adopting purely Western values.

But Laura Kellogg had seen the values of the modern U.S. in the ravages of industrial capitalism in New York, impoverishing the working-class.

What sort of ‘civilisation’ was this to follow?

“No, I cannot see that everything the white man does is to be copied.”

Instead, Kellogg argued that the U.S. could do with being ‘civilised’ by indigenous cultural practices.

When white women won the right to vote nationally in 1920 with the ratification of the 19th Amendment, Kellogg pointed out that Iroquois society, with its system of clan mothers, had included women in the political process since long before Europeans invaded North America:

“It is a cause of astonishment to us that you white women are only now, in this twentieth century, claiming what has been the Indian woman’s privilege as far back as history traces.”

Kellogg also co-founded, in 1911, the Society of American Indians, which helped to promote Native American identity and cultural activity in the U.S.

Instead of the imagined deficiencies of indigenous culture, then, Kellogg argued that the impoverishment of modern Native Americans was due to the political economy of settler colonialism.

Specifically, it was a matter of land.

Laura Kellogg inherited the radical legacy of Native American warriors and activists like Crazy Horse

The Iroquois, like all the other indigenous peoples under U.S. rule, had had most of their land stolen from them by European settlers since the late eighteenth century, including by gross violation of treaties signed with the U.S. federal government.

In 1922, a New York assemblyman called Edward Everett published a report – quickly repudiated by his white colleagues – claiming that the Six Nations of the Iroquois were entitled to 6 million acres of land in New York state due to illegal land theft since 1784.

Laura Kellogg spent the 1910s and 1920s lobbying the federal government to return those indigenous lands.

She believed that, with more land and more political self-government, indigenous communities in the U.S. could achieve economic self-sufficiency and cultural resilience.

Kellogg even took some ideas from the contemporary ‘garden city movement’ in European urban planning, which aimed for an ideal balance between rural and urban life, rather than the unhinged destructiveness and misery of full-scale capitalist industrialisation.

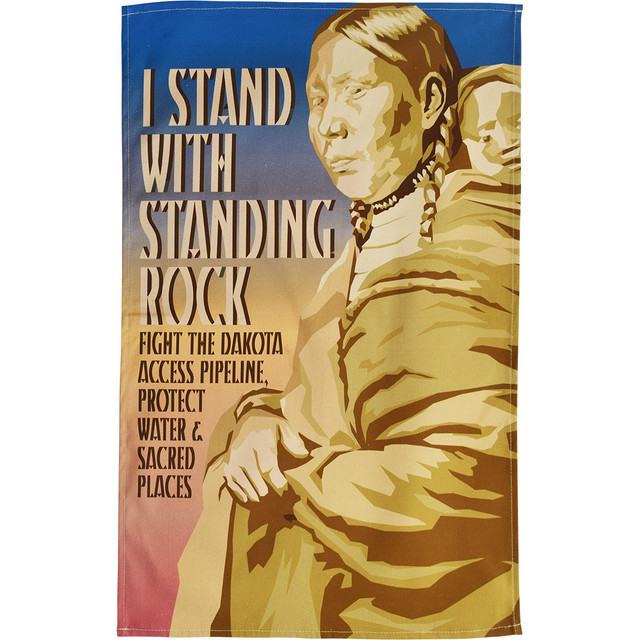

Kellogg's legacy lives on in contemporary movements to protect indigenous land, like the 2016 protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline

See the Standing Rock tea towel

Kellogg’s vision of revitalised Native American communities, embracing their own rich cultural traditions and self-governing the economic resources of their restored lands, hoped for a major indigenous revival in the U.S. after centuries of conquest, genocide, and marginalisation.

Kellogg’s specific plan was not realised due to the reactionary opposition of state governments and land-hungry corporations in places like Oklahoma and New York.

But she remains a crucial and often forgotten precursor of the radical American Indian Movement of the later twentieth century, as the struggle carried on.