What Freedom Really Looked Like: Women's Suffrage in America

Posted by Pete on Aug 27th 2024

Native Americans were key allies in the struggle for women's suffrage in the United States

On the 18th of August, 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution went into effect when it was ratified by the last of the holdout states.

The Amendment prohibited states from denying citizens the right to vote on the basis of sex, effectively recognising American women’s right to vote after a century of widespread disenfranchisement.

This was the culmination of

first-wave feminist activism in the U.S.

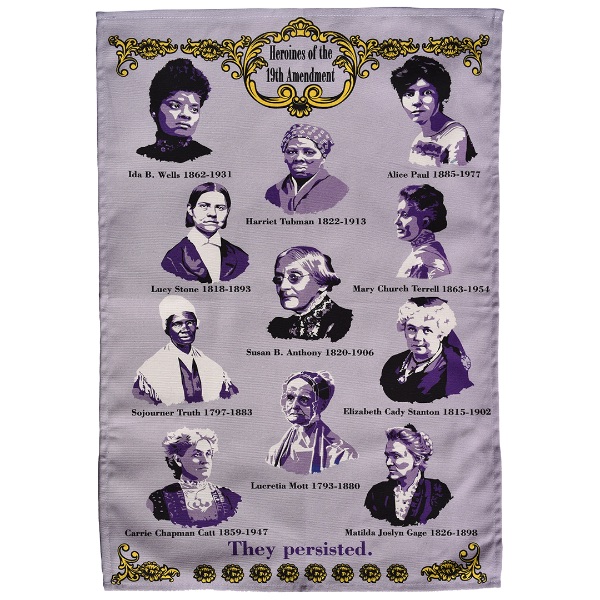

The struggle for women's suffrage in the United States involved a huge coalition of different activists

See the 19th Amendment Heroines tea towel

But the women’s suffrage movement had not carried on its struggle in isolation.

Since it broke onto the political scene at

Seneca Falls in 1848, the American feminist movement had made a habit of building coalitions with other oppressed groups in the U.S.

Nineteenth-century feminists often joined abolitionists in the

struggle for black freedom, and vice-versa.

And the women’s suffrage movement worked together with socialist and labour activists, on the basis of a shared commitment to human equality.

But one of the suffrage movement’s most significant alliances was with the anticolonial struggle of Native Americans.

In the long fight for the Nineteenth Amendment, Native American women were on the frontline.

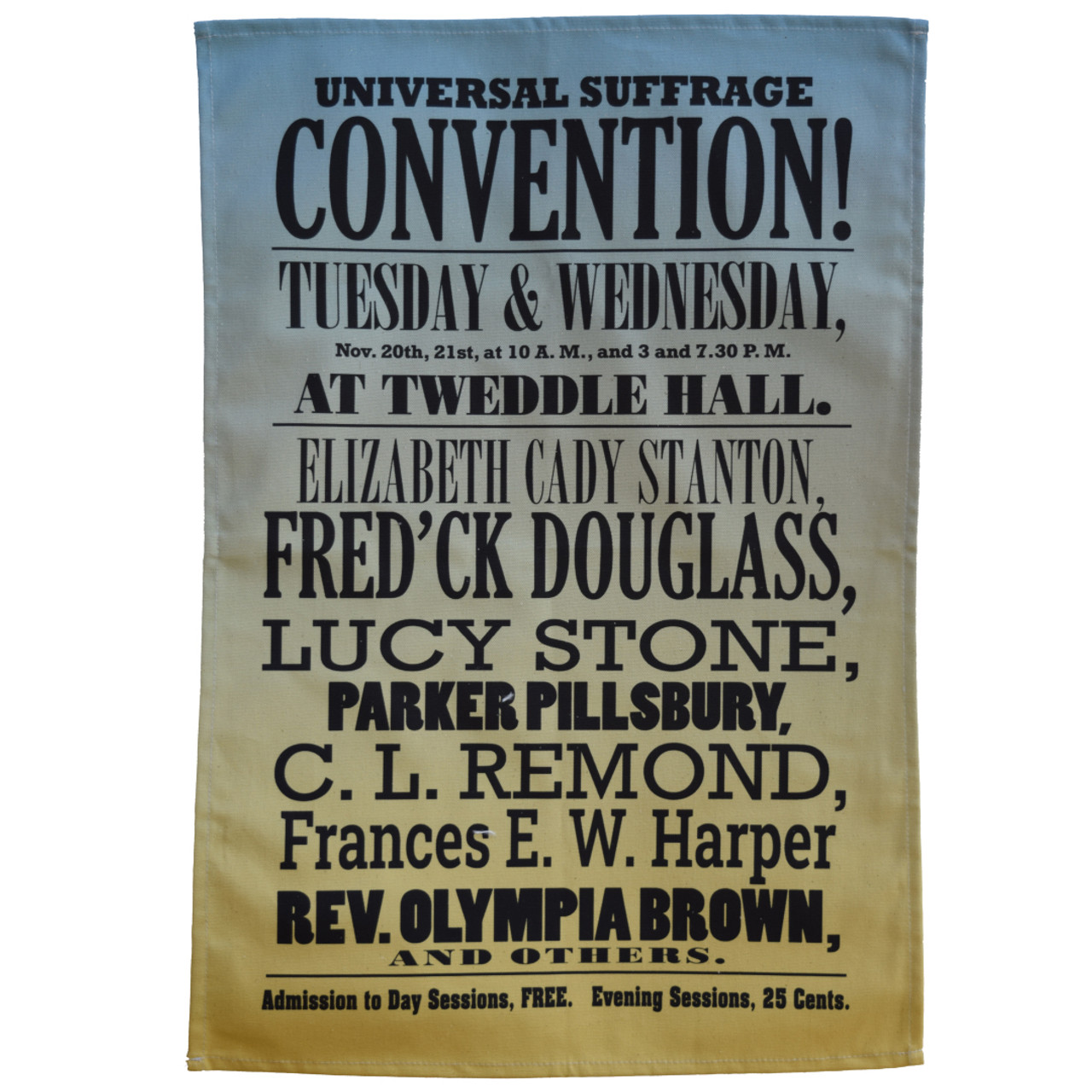

Frederick Douglass and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were keynote speakers at the Seneca Falls Convention which launched the women's suffrage movement in the United States

See the Frederick Douglass tea towel

In the first instance, Native American societies were seen by – and shown to – early white feminists as an alternative, non-patriarchal model of social organisation

The very societies unjustly conquered by the U.S. in the name of ‘civilisation’ were actually more civilised than their conqueror, insofar as indigenous women were not denied an equal role in political and social life on account of their gender.

Several of the Seneca Falls Convention pioneers, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, visited the nearby Iroquois communities in New York state, and they marvelled at the political rights of women there.

The relatively egalitarian model of gender relations practised by such indigenous societies had a lasting impact on several white feminists during the suffrage struggle.

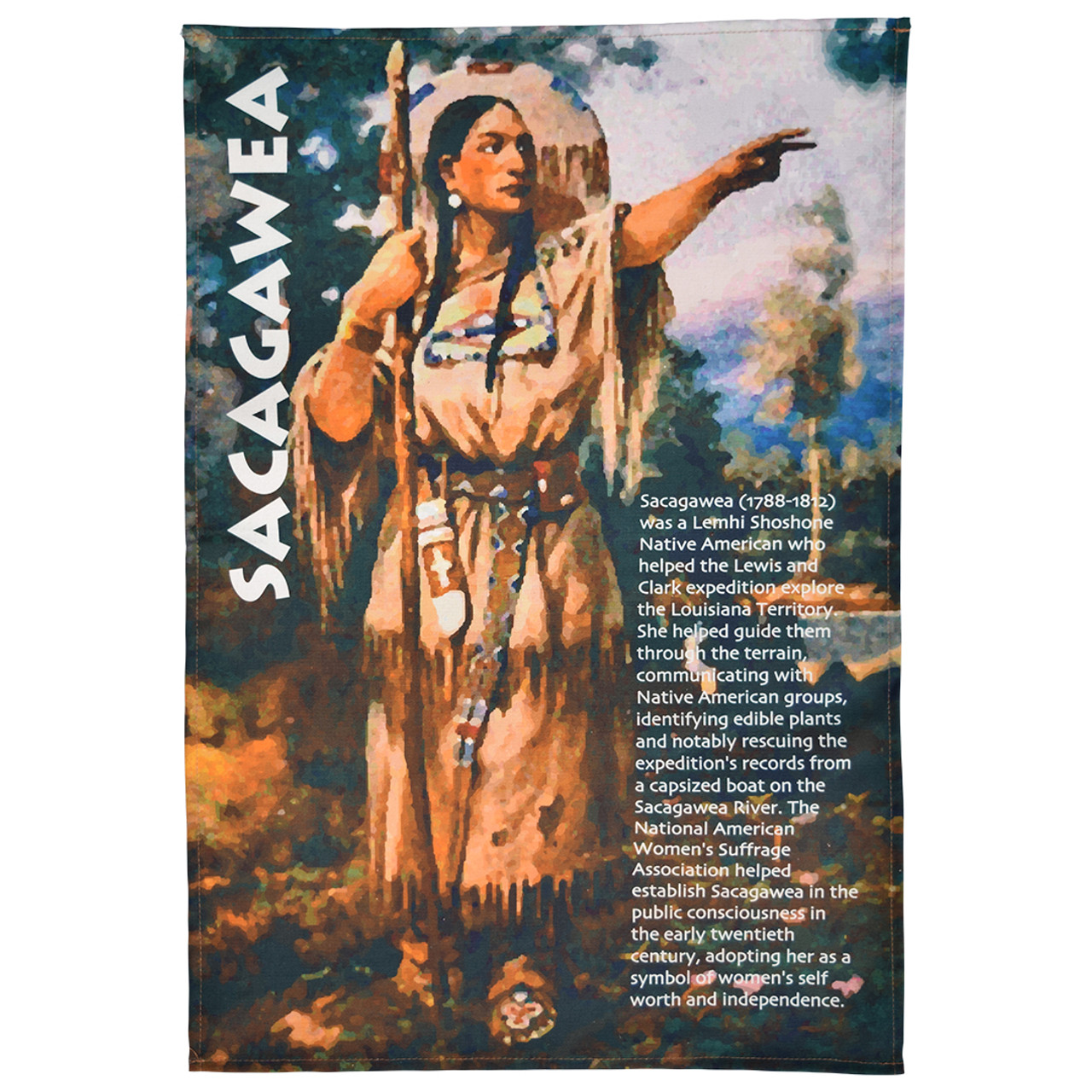

In Oregon, a campaign to build a statue of Sacagawea of the Lemhi Shoshone tribe, to recognise her as a founding hero of the American Republic, sparked the suffrage movement in that state.

And the New York suffragist, Matilda Joslyn Gage, saw the Iroquois as an example of how egalitarian gender relations led to social and international peace.

As Louise McDonald Herne of the Mohawk Nation reflected on the eventual passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, it was Native American women who had:

“showed white women what freedom and liberty really looked like.”

The National American Women's Suffrage Association helped adopted Sacagawea as a symbol of women's independence

But far from being just a source of inspiration, Native Americans were also active participants in the struggle for women’s suffrage.

In Oklahoma, in 1904, the Chickasaw Nation agreed to work with that state’s Woman Suffrage Association.

And individual Native American women were also active suffragists, like Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin of the Métis Turtle Mountain Band, who took part in the

1913 Women's March in Washington D.C.

But despite their contribution to the struggle, the Nineteenth Amendment left Native American women behind.

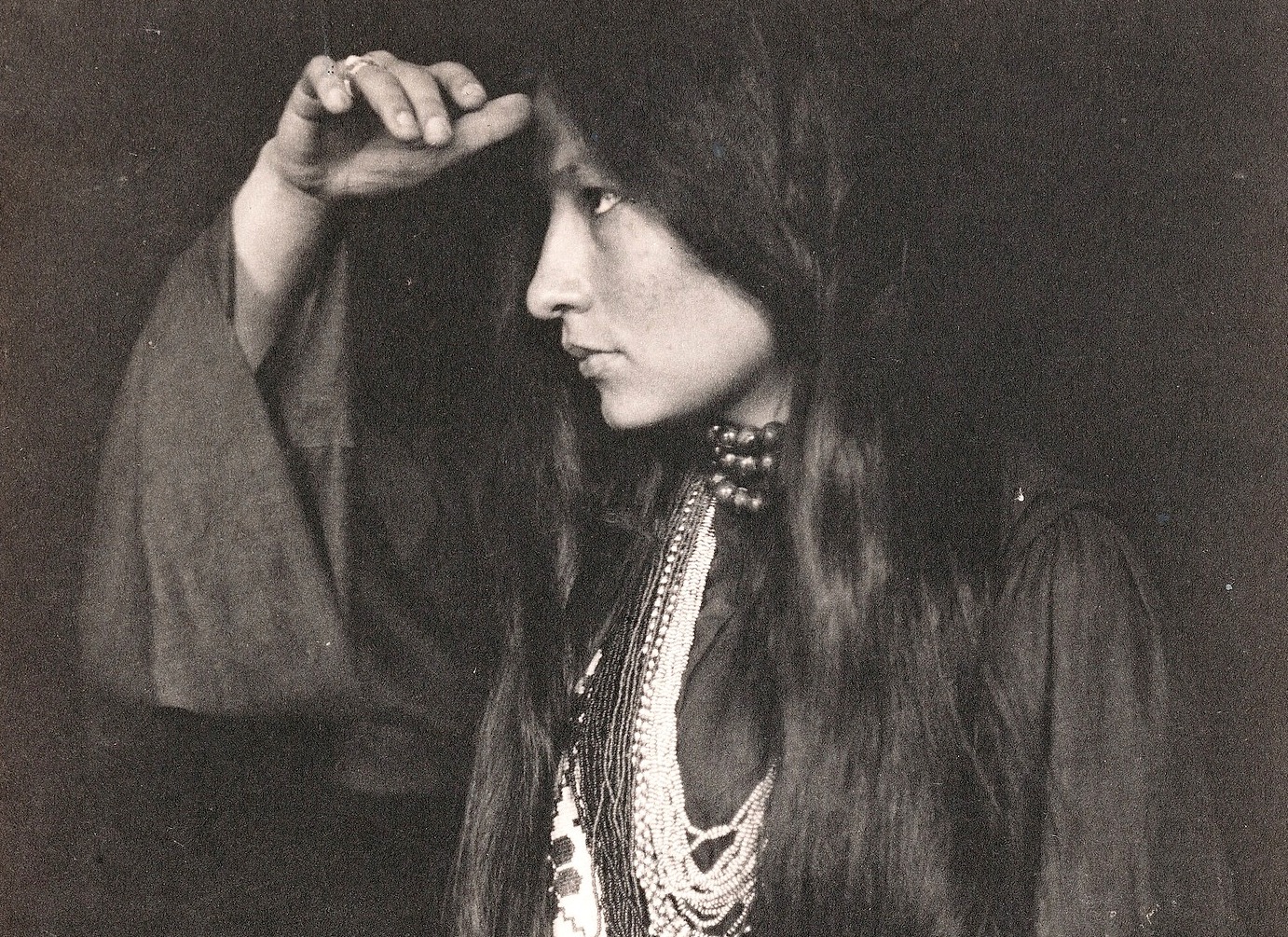

As the Yankton Sioux activist Zitkala-Sa pointed out, indigenous women were still not allowed to vote after 1920 because, like indigenous men, they were denied the status and rights of U.S. citizens.

Similarly, the Nineteenth Amendment had failed black women across the U.S. South, where they continued to be barred from voting for decades by racist state governments.

The Nineteenth Amendment had not resolved the gendered injustices of American society rooted in colonial oppression and racism.

Even after a 1924 law was passed to expand Native American citizenship, many indigenous women had to continue struggling for their right to vote, against racist state laws, until the 1950s.

The Nineteenth Amendment was a major step – but hardly the last step – on the road to the liberation of all women in the United States.

And the same multiracial and intersectional solidarity which helped to win the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 remains the best bet for defending and expanding equality today.